Was The Low Voter Turnout in Virginia What Ben Franklin Warned Us About?

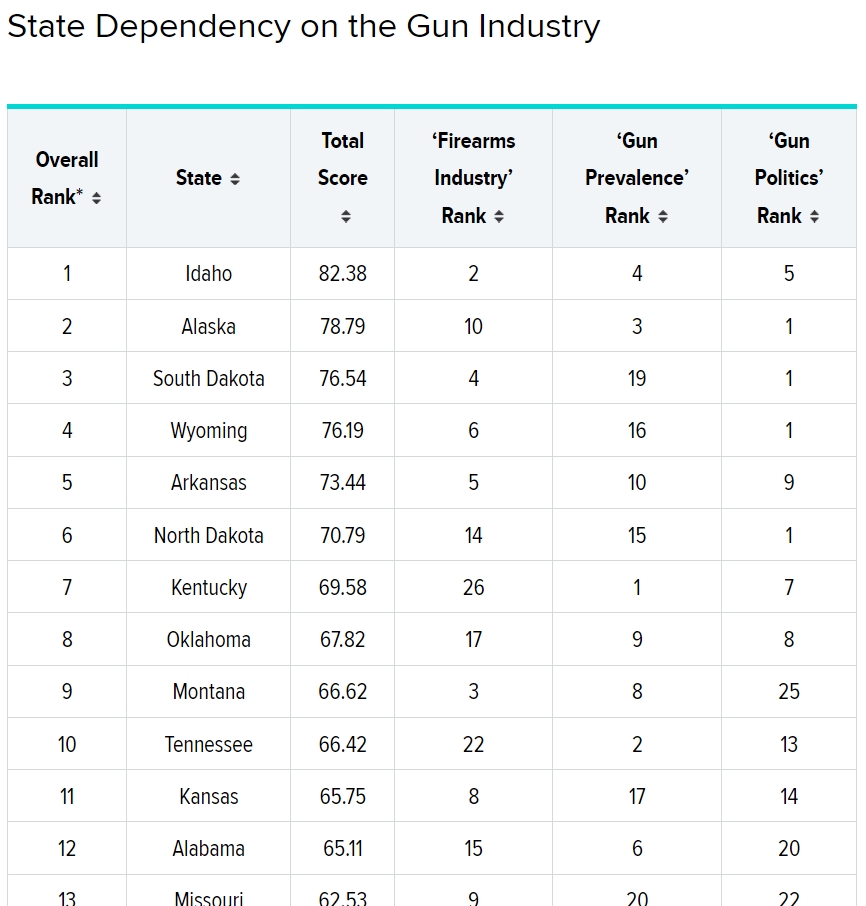

United States That Are Most Dependent on The Firearm Industry at WalletHub – Interactive Map

Source: WalletHub – April/2019 – States Most Dependent on the Gun Industry

Gun sales have been down since Donald Trump won the White House, with a 6.1 percent decline in 2018 alone. And while that’s good news to some, it could be a bad sign for state economies relying heavily on the firearms industry. By one estimate, guns contributed more than $52 billion to the U.S. economy and generated over $6.8 billion in federal and state taxes in 2018.

In 2018, gun crime was a high-profile political issue, highlighted by incidents such as the February Parkland, FL school shooting and the October Tree of Life Synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh. Many states passed new gun laws and gun control groups outspent gun rights groups. 2019 has had its own share of violent incidents as well, such as the Aurora, IL workplace shooting in February. In addition, several new laws have been passed this year, including a federal ban on “bump-stocks.”

In light of the recent developments in the firearms industry and debates on how, if at all, it should be restricted, WalletHub compared the economic impact of guns on each of the 50 states to determine which among them leans most heavily on the gun business, both directly for jobs and political contributions and indirectly through ownership. Read on for our findings, methodology and expert commentary from a panel of researchers.

Source: https://wallethub.com/edu/states-most-dependent-on-the-gun-industry/18719/

Lost Firearms Freedom & Gun Control in America – Poll: What Should We Take Back First?

Join Now to engage in our Firearms Friendly Community with now thousands of Firearms Friendly Members In Dozens of Firearms Friendly Groups!

Lets looks at what we’ve lost so far to come up with a list that we can all agree on to take back first and how to do it.

Time.com – A Timeline of the Major Gun Control Laws in America.

1791

On Dec. 15, 1791, ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution — eventually known as the Bill of Rights — were ratified. The second of them said: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

1934

The first piece of national gun control legislation was passed on June 26, 1934. The National Firearms Act (NFA) — part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “New Deal for Crime“— was meant to curtail “gangland crimes of that era such as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.”

The NFA imposed a tax on the manufacturing, selling, and transporting of firearms listed in the law, among them short-barrel shotguns and rifles, machine guns, firearm mufflers and silencers. Due to constitutional flaws, the NFA was modified several times. The $200 tax, which was high for the era, was put in place to curtail the transfer of these weapons.

1938

The Federal Firearms Act (FFA) of 1938 required gun manufacturers, importers, and dealers to obtain a federal firearms license. It also defined a group of people, including convicted felons, who could not purchase guns, and mandated that gun sellers keep customer records. The FFA was repealed in 1968 by the Gun Control Act (GCA), though many of its provisions were reenacted by the GCA.

1939

In 1939 the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case United States v. Miller, ruling that through the National Firearms Act of 1934, Congress could regulate the interstate selling of a short barrel shotgun. The court stated that there was no evidence that a sawed off shotgun “has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia,” and thus “we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument.”

1968

Following the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Attorney General and U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed for the passage of the Gun Control Act of 1968. The GCA repealed and replaced the FFA, updated Title II of the NFA to fix constitutional issues, added language about “destructive devices” (such as bombs, mines and grenades) and expanded the definition of “machine gun.”

Overall the bill banned importing guns that have “no sporting purpose,” imposed age restrictions for the purchase of handguns (gun owners had to be 21), prohibited felons, the mentally ill, and others from purchasing guns, required that all manufactured or imported guns have a serial number, and according to the ATF, imposed “stricter licensing and regulation on the firearms industry.”

1986

In 1986 the Firearm Owners Protection Act was passed by Congress. The law mainly enacted protections for gun owners — prohibiting a national registry of dealer records, limiting ATF inspections to once per year (unless there are multiple infractions), softening what is defined as “engaging in the business” of selling firearms, and allowing licensed dealers to sell firearms at “gun shows” in their state. It also loosened regulations on the sale and transfer of ammunition. The bill also codified some gun control measures, including expanding the GCA to prohibit civilian ownership or transfer of machine guns made after May 19, 1986, and redefining “silencer” to include parts intended to make silencers.

1993

The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993 is named after White House press secretary James Brady, who was permanently disabled from an injury suffered during an attempt to assassinate President Ronald Reagan. (Brady died in 2014). It was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. The law, which amends the GCA, requires that background checks be completed before a gun is purchased from a licensed dealer, manufacturer or importer. It established the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), which is maintained by the FBI.

1994

Tucked into the sweeping and controversial Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, signed by President Clinton in 1994, is the subsection titled Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act. This is known as the assault weapons ban — a temporary prohibition in effect from September of 1994 to September of 2004. Multiple attempts to renew the ban have failed.

The provisions of the bill outlawed the ability to “manufacture, transfer, or possess a semiautomatic assault weapon,” unless it was “lawfully possessed under Federal law on the date of the enactment of this subsection.” Nineteen military-style or “copy-cat” assault weapons—including AR-15s, TEC-9s, MAC-10s, etc.—could not be manufactured or sold. It also banned “certain high-capacity ammunition magazines of more than ten rounds,” according to a U.S. Department of Justice Fact Sheet.

2003

The Tiahrt Amendment, proposed by Todd Tiahrt (R-Kan.), prohibited the ATF from publicly releasing data showing where criminals purchased their firearms and stipulated that only law enforcement officers or prosecutors could access such information.

“The law effectively shields retailers from lawsuits, academic study and public scrutiny,” The Washington Post wrote in 2010. “It also keeps the spotlight off the relationship between rogue gun dealers and the black market in firearms.”

There have been efforts to repeal this amendment.

2005

In 2005, the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act was signed by President George W. Bush to prevent gun manufacturers from being named in federal or state civil suits by those who were victims of crimes involving guns made by that company. The first provision of this law is “to prohibit causes of action against manufacturers, distributors, dealers, and importers of firearms or ammunition products, and their trade associations, for the harm solely caused by the criminal or unlawful misuse of firearm products or ammunition products by others when the product functioned as designed and intended.” It also dismissed pending cases on October 26, 2005.

2008

District of Columbia v. Heller essentially changed a nearly 70-year precedent set by Miller in 1939. While the Miller ruling focused on the “well regulated militia” portion of the Second Amendment (known as the “collective rights theory” and referring to a state’s right to defend itself), Heller focused on the “individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia.”

Heller challenged the constitutionality of a 32-year-old handgun ban in Washington, D.C., and found, “The handgun ban and the trigger-lock requirement (as applied to self-defense) violate the Second Amendment.”

It did not however nullify other gun control provisions. “The Court’s opinion should not be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms,” stated the ruling.

Source: https://time.com/5169210/us-gun-control-laws-history-timeline/

Find, Share and Join Dozens or Create Your Own Gun-Friendly Groups at FirearmsFriendly.com

What Do YOU Believe Should Be The Core Values of Someone Claiming That They Are Firearms Friendly?

How do you describe someone who is firearms friendly? What must they do specifically to become or remain firearms friendly?

Sheriff Richard Mack Says “let’s all calm down” on The Virginia Second Amendment Situation

From Sheriff Richard Mack on Facebook’s Post regarding the political situation around the 2nd Amendment in Virginia.

“Yes, there has been a great deal of hyperbole (hype) about the political battles going on in the great State of Virginia. Indeed, this hype has been coming from all sides, including some from “patriot” groups and well-meaning gun rights organizations. Of course, we have seen the same ol same ol from the leftist media that has added fuel to the frenzy. The truth is that the next Civil War is not about to happen and an armed standoff is NOT even close to being the solution. Everyone needs to calm down and let Virginia work this out. There are lots of things happening there that are absolutely wonderful, perhaps even miraculous.

First, the Governor of VA, as horrible as he may be, is not calling out the National Guard to quell protests or to enforce his gun control edicts. The Adjutant General of the Va National Guard, Timothy P. Williams, said they have received no request from the Governor to serve in a law enforcement capacity. In fact, the Governor did not make the comment regarding the utilization of the National Guard, it came from Democrat VA Rep. Donald McEachin, who suggested the Governor might need to call out the Guard to enforce Gun Control. McEachin even mentioned the VA sheriffs who are opposing gun control.

This is the good news. A huge majority of the Virginia sheriffs have strongly indicated that they will not enforce any of these Unconstitutional “laws.” Not only do they violate the United States Constitution, but the Virginia Constitution as well. Now get this! The Virginia Constitution is even more direct and emphatic than is the Federal Bill of Rights regarding the Right of the People to Keep and Bear Arms. It states: “That a well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defense of a free state, therefore, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed…”

Again we have lawmakers breaking the law, violating their oaths, and showing a complete disdain for the Constitutions. On the other hand we now have the sheriffs of Virginia standing strong and doing their jobs, keeping their oaths to serve, protect, uphold, and defend. Furthermore, there are now over 105 cities and counties in VA that have declared themselves to be Second Amendment Sanctuaries. This is amazing, and as I said, perhaps even Miraculous!

Martin Luther King said, “One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” This is a very true and principled statement and the sheriffs of VA or anywhere in this country, have no lawful or moral obligation to enforce unjust or unconstitutional laws; quite the contrary. Sheriffs and Chiefs of Police in the States of Washington and New Mexico are also taking similar stands. Several other States have done likewise. Even the famous city of Tombstone, AZ has declared itself a safe haven for the Second Amendment. These actions by these American hero Public Officials and Peace Officers are not creating a “Civil War,” they are preventing one. They are not creating an atmosphere of violence, they are preventing violence.

So, let’s all calm down and let the sheriffs in VA do their jobs and be ready to support them if and when needed. They will let us know if they need some assistance. Thus far, they have not asked for any help and we should all respect that. There is no “Civil War” brewing there, just some ignorant rhetoric from vapid politicians.”

Source: https://www.facebook.com/SheriffMack/posts/1795779837219951

___________________________________________________

Richard Ivan Mack (born 1952) is the former sheriff of Graham County, Arizona and a political activist. He is known for his role in a successful lawsuit brought against the federal government of the United States which alleged that portions of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act violated the United States Constitution. He is a former lobbyist for Gun Owners of America (GOA) and a two-time candidate for United States Congress. Mack is also the founder of Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA), and established the “County Sheriff Project” movement, both of whom reaffirm the constitutional power to refuse to enforce federal laws.[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Mack

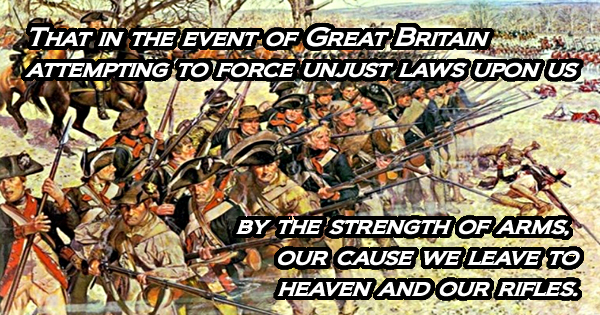

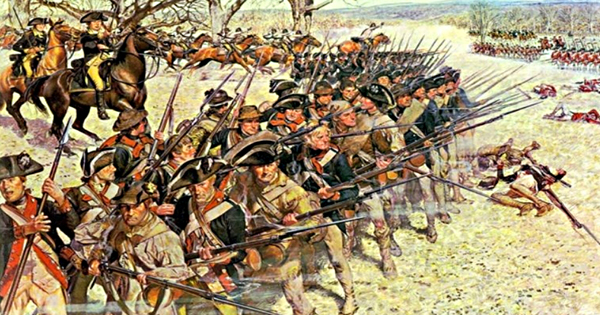

The First American Revolution Began as Resistance To Attempted British Firearms and Gun Powder Confiscation

DaveKopel.org – The American Revolution against British Gun Control

DaveKopel.org – The American Revolution against British Gun Control

This Article reviews the British gun control program that precipitated the American Revolution: the 1774 import ban on firearms and gunpowder; the 1774-75 confiscations of firearms and gunpowder; and the use of violence to effectuate the confiscations. It was these events that changed a situation of political tension into a shooting war. Each of these British abuses provides insights into the scope of the modern Second Amendment.

Furious at the December 1773 Boston Tea Party, Parliament in 1774 passed the Coercive Acts. The particular provisions of the Coercive Acts were offensive to Americans, but it was the possibility that the British might deploy the army to enforce them that primed many colonists for armed resistance. The Patriots of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, resolved: “That in the event of Great Britain attempting to force unjust laws upon us by the strength of arms, our cause we leave to heaven and our rifles.” A South Carolina newspaper essay, reprinted in Virginia, urged that any law that had to be enforced by the military was necessarily illegitimate.

The Royal Governor of Massachusetts, General Thomas Gage, had forbidden town meetings from taking place more than once a year. When he dispatched the Redcoats to break up an illegal town meeting in Salem, 3000 armed Americans appeared in response, and the British retreated. Gage’s aide John Andrews explained that everyone in the area aged 16 years or older owned a gun and plenty of gunpowder.

Military rule would be difficult to impose on an armed populace. Gage had only 2,000 troops in Boston. There were thousands of armed men in Boston alone, and more in the surrounding area. One response to the problem was to deprive the Americans of gunpowder.

Modern “smokeless” gunpowder is stable under most conditions. The “black powder” of the 18th Century was far more volatile. Accordingly, large quantities of black powder were often stored in a town’s “powder house,” typically a reinforced brick building. The powder house would hold merchants’ reserves, large quantities stored by individuals, as well as powder for use by the local militia. Although colonial laws generally required militiamen (and sometimes all householders, too) to have their own firearm and a minimum quantity of powder, not everyone could afford it. Consequently, the government sometimes supplied “public arms” and powder to individual militiamen. Policies varied on whether militiamen who had been given public arms would keep them at home. Public arms would often be stored in a special armory, which might also be the powder house.

Before dawn on September 1, 1774, 260 of Gage’s Redcoats sailed up the Mystic River and seized hundreds of barrels of powder from the Charlestown powder house.

The “Powder Alarm,” as it became known, was a serious provocation. By the end of the day, 20,000 militiamen had mobilized and started marching towards Boston. In Connecticut and Western Massachusetts, rumors quickly spread that the Powder Alarm had actually involved fighting in the streets of Boston. More accurate reports reached the militia companies before that militia reached Boston, and so the war did not begin in September. The message, though, was unmistakable: If the British used violence to seize arms or powder, the Americans would treat that violent seizure as an act of war, and would fight. And that is exactly what happened several months later, on April 19, 1775.

Five days after the Powder Alarm, on September 6, the militia of the towns of Worcester County assembled on the Worcester Common. Backed by the formidable array, the Worcester Convention took over the reins of government, and ordered the resignations of all militia officers, who had received their commissions from the Royal Governor. The officers promptly resigned and then received new commissions from the Worcester Convention.

That same day, the people of Suffolk County (which includes Boston) assembled and adopted the Suffolk Resolves. The 19-point Resolves complained about the Powder Alarm, and then took control of the local militia away from the Royal Governor (by replacing the Governor’s appointed officers with officers elected by the militia) and resolved to engage in group practice with arms at least weekly.

The First Continental Congress, which had just assembled in Philadelphia, unanimously endorsed the Suffolk Resolves and urged all the other colonies to send supplies to help the Bostonians.

Governor Gage directed the Redcoats to begin general, warrantless searches for arms and ammunition. According to the Boston Gazette, of all General Gage’s offenses, “what most irritated the People” was “seizing their Arms and Ammunition.”

When the Massachusetts Assembly convened, General Gage declared it illegal, so the representatives reassembled as the “Provincial Congress.” On October 26, 1774, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress adopted a resolution condemning military rule, and criticizing Gage for “unlawfully seizing and retaining large quantities of ammunition in the arsenal at Boston.” The Provincial Congress urged all militia companies to organize and elect their own officers. At least a quarter of the militia (the famous Minute Men) were directed to “equip and hold themselves in readiness to march at the shortest notice.” The Provincial Congress further declared that everyone who did not already have a gun should get one, and start practicing with it diligently.

In flagrant defiance of royal authority, the Provincial Congress appointed a Committee of Safety and vested it with the power to call forth the militia. The militia of Massachusetts was now the instrument of what was becoming an independent government of Massachusetts.

Lord Dartmouth, the Royal Secretary of State for America, sent Gage a letter on October 17, 1774, urging him to disarm New England. Gage replied that he would like to do so, but it was impossible without the use of force. After Gage’s letter was made public by a reading in the British House of Commons, it was publicized in America as proof of Britain’s malign intentions.

Two days after Lord Dartmouth dispatched his disarmament recommendation, King George III and his ministers blocked importation of arms and ammunition to America. Read literally, the order merely required a permit to export arms or ammunition from Great Britain to America. In practice, no permits were granted.

Meanwhile, Benjamin Franklin was masterminding the surreptitious import of arms and ammunition from the Netherlands, France, and Spain.

The patriotic Boston Committee of Correspondence learned of the arms embargo and promptly dispatched Paul Revere to New Hampshire, with the warning that two British ships were headed to Fort William and Mary, near Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to seize firearms, cannons, and gunpowder. On December 14, 1774, 400 New Hampshire patriots preemptively captured all the material at the fort. A New Hampshire newspaper argued that the capture was prudent and proper, reminding readers that the ancient Carthaginians had consented to “deliver up all their Arms to the Romans” and were decimated by the Romans soon after.

In Parliament, a moderate minority favored conciliation with America. Among the moderates was the Duke of Manchester, who warned that America now had three million people, and most of them were trained to use arms. He was certain they could produce a stronger army than Great Britain.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress offered to purchase as many arms and bayonets as could be delivered to the next session of the Congress. Massachusetts also urged American gunsmiths “diligently to apply themselves” to making guns for everyone who did not already have a gun. A few weeks earlier, the Congress had resolved: “That it be strongly recommended, to all the inhabitants of this colony, to be diligently attentive to learning the use of arms . . . .”

Derived from political and legal philosophers such as John Locke, Hugo Grotius, and Edward Coke, the ideology underlying all forms of American resistance was explicitly premised on the right of self-defense of all inalienable rights; from the self-defense foundation was constructed a political theory in which the people were the masters and government the servant, so that the people have the right to remove a disobedient servant.

The British government was not, in a purely formal sense, attempting to abolish the Americans’ common law right of self-defense. Yet in practice, that was precisely what the British were attempting. First, by disarming the Americans, the British were attempting to make the practical exercise of the right of personal self-defense much more difficult. Second, and more fundamentally, the Americans made no distinction between self-defense against a lone criminal or against a criminal government. To the Americans, and to their British Whig ancestors, the right of self-defense necessarily implied the right of armed self-defense against tyranny.

The troubles in New England inflamed the other colonies. Patrick Henry’s great speech to the Virginia legislature on March 23, 1775, argued that the British plainly meant to subjugate America by force. Because every attempt by the Americans at peaceful reconciliation had been rebuffed, the only remaining alternatives for the Americans were to accept slavery or to take up arms. If the Americans did not act soon, the British would soon disarm them, and all hope would be lost. “The millions of people, armed in the holy cause of liberty, and in such a country as that which we possess, are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us,” he promised.

The Convention formed a committee–including Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson–“to prepare a plan for the embodying, arming, and disciplining such a number of men as may be sufficient” to defend the commonwealth. The Convention urged “that every Man be provided with a good Rifle” and “that every Horseman be provided . . . with Pistols and Holsters, a Carbine, or other Firelock.” When the Virginia militiamen assembled a few weeks later, many wore canvas hunting shirts adorned with the motto “Liberty or Death.”

In South Carolina, patriots established a government, headed by the “General Committee.” The Committee described the British arms embargo as a plot to disarm the Americans in order to enslave them. Thus, the Committee recommended that “all persons” should “immediately” provide themselves with a large quantity of ammunition.

Without formal legal authorization, Americans began to form independent militia, outside the traditional chain of command of the royal governors. In Virginia, George Washington and George Mason organized the Fairfax Independent Militia Company. The Fairfax militiamen pledged that “we will, each of us, constantly keep by us” a firelock, six pounds of gunpowder, and twenty pounds of lead. Other independent militia embodied in Virginia along the same model. Independent militia also formed in Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Maryland, and South Carolina, choosing their own officers.

John Adams praised the newly constituted Massachusetts militia, “commanded through the province, not by men who procured their commissions from a governor as a reward for making themselves pimps to his tools.”

The American War of Independence began on April 19, 1775, when 700 Redcoats under the command of Major John Pitcairn left Boston to seize American arms at Lexington and Concord.

The militia that assembled at the Lexington Green and the Concord Bridge consisted of able-bodied men aged 16 to 60. They supplied their own firearms, although a few poor men had to borrow a gun. Warned by Paul Revere and Samuel Dawes of the British advance, the young women of Lexington assembled cartridges late into the evening of April 18.

At dawn, the British confronted about 200 militiamen at Lexington. “Disperse you Rebels–Damn you, throw down your Arms and disperse!” ordered Major Pitcairn. The Americans were quickly routed.

With a “huzzah” of victory, the Redcoats marched on to Concord, where one of Gage’s spies had told him that the largest Patriot reserve of gunpowder was stored. At Concord’s North Bridge, the town militia met with some of the British force, and after a battle of two or three minutes, drove off the British.

Notwithstanding the setback at the bridge, the Redcoats had sufficient force to search the town for arms and ammunition. But the main powder stores at Concord had been hauled to safety before the Redcoats arrived.

When the British began to withdraw back to Boston, things got much worse for them. Armed Americans were swarming in from nearby towns. They would soon outnumber the British 2:1. Although some of the Americans cohered in militia units, a great many fought on their own, taking sniper positions wherever opportunity presented itself. Only British reinforcements dispatched from Boston saved the British expedition from annihilation–and the fact that the Americans started running out of ammunition and gun powder.

One British officer reported: “These fellows were generally good marksmen, and many of them used long guns made for Duck-Shooting.” On a per-shot basis, the Americans inflicted higher casualties than had the British regulars.

That night, the American militiamen began laying siege to Boston, where General Gage’s standing army was located. At dawn, Boston had been the base from which the King’s army could project force into New England. Now, it was trapped in the city, surrounded by people in arms.

Two days later in Virginia, royal authorities confiscated 20 barrels of gunpowder from the public magazine in Williamsburg and destroyed the public firearms there by removing their firing mechanisms. In response to complaints, manifested most visibly by the mustering of a large independent militia led by Patrick Henry, Governor Dunmore delivered a legal note promising to pay restitution.

At Lexington and Concord, forcible disarmament had not worked out for the British. So back in Boston, Gage set out to disarm the Bostonians a different way.

On April 23, 1775, Gage offered the Bostonians the opportunity to leave town if they surrendered their arms. The Boston Selectmen voted to accept the offer, and within days, 2,674 guns were deposited, one gun for every two adult male Bostonians.

Gage thought that many Bostonians still had guns, and he refused to allow the Bostonians to leave. Indeed, a large proportion of the surrendered guns were “training arms”–large muskets with bayonets, that would be difficult to hide. After several months, food shortages in Boston convinced Gage to allow easier emigration from the city.

Gage’s disarmament program incited other Americans to take up arms. Benjamin Franklin, returning to Philadelphia after an unsuccessful diplomatic trip to London, “was highly pleased to find the Americans arming and preparing for the worst events.”

The government in London dispatched more troops and three more generals to America: William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne. The generals arrived on May 25, 1775, with orders from Lord Dartmouth to seize all arms in public armories, or which had been “secretly collected together for the purpose of aiding Rebellions.”

The war underway, the Americans captured Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York. At the June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill, the militia held its ground against the British regulars and inflicted heavy casualties, until they ran out of gunpowder and were finally driven back. (Had Gage not confiscated the gunpowder from the Charleston Powder House the previous September, the Battle of Bunker Hill probably would have resulted in an outright defeat of the British.)

On June 19, Gage renewed his demand that the Bostonians surrender their arms, and he declared that anyone found in possession of arms would be deemed guilty of treason.

Meanwhile, the Continental Congress had voted to send ten companies of riflemen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to aid the Massachusetts militia.

On July 6, 1775, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, written by Thomas Jefferson and the great Pennsylvania lawyer John Dickinson. Among the grievances were General Gage’s efforts to disarm the people of Lexington, Concord, and Boston.

Two days later, the Continental Congress sent an open letter to the people of Great Britain warning that “men trained to arms from their Infancy, and animated by the Love of Liberty, will afford neither a cheap or easy conquest.”

The Swiss immigrant John Zubly, who was serving as a Georgia delegate to the Continental Congress, wrote a pamphlet entitled Great Britain’s Right to Tax . . . By a Swiss, which was published in London and Philadelphia. He warned that “in a strong sense of liberty, and the use of fire-arms almost from the cradle, the Americans have vastly the advantage over men of their rank almost every where else.” Indeed, children were “shouldering the resemblance of a gun before they are well able to walk.” “The Americans will fight like men, who have everything at stake,” and their motto was “DEATH OR FREEDOM.” The town of Gorham, Massachusetts (now part of the State of Maine), sent the British government a warning that even “many of our Women have been used to handle the Cartridge and load the Musquet.”

It was feared that the Massachusetts gun confiscation was the prototype for the rest of America. For example, a newspaper article published in three colonies reported that when the new British generals arrived, they would order everyone in America “to deliver up their arms by a certain stipulated day.”

The events of April 19 convinced many more Americans to arm themselves and to embody independent militia. A report from New York City observed that “the inhabitants there are arming themselves . . . forming companies, and taking every method to defend our rights. The like spirit prevails in the province of New Jersey, where a large and well disciplined militia are now fit for action.”

In Virginia, Lord Dunmore observed: “Every County is now Arming a Company of men whom they call an independent Company for the avowed purpose of protecting their Committee, and to be employed against Government if occasion require.” North Carolina’s Royal Governor Josiah Martin issued a proclamation outlawing independent militia, but it had little effect.

A Virginia gentleman wrote a letter to a Scottish friend explaining in America:

We are all in arms, exercising and training old and young to the use of the gun. No person goes abroad without his sword, or gun, or pistols. . . . Every plain is full of armed men, who all wear a hunting shirt, on the left breast of which are sewed, in very legible letters, “Liberty or Death.”

The British escalated the war. Royal Admiral Samuel Graves ordered that all seaports north of Boston be burned.

When the British navy showed up at what was then known as Falmouth, Massachusetts (today’s Portland, Maine), the town attempted to negotiate. The townspeople gave up eight muskets, which was hardly sufficient, and so Falmouth was destroyed by naval bombardment.

The next year, the 13 Colonies would adopt the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration listed the tyrannical acts of King George III, including his methods for carrying out gun control: “He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our people.”

As the war went on, the British always remembered that without gun control, they could never control America. In 1777, with British victory seeming likely, Colonial Undersecretary William Knox drafted a plan entitled “What Is Fit to Be Done with America?” To ensure that there would be no future rebellions, “[t]he Militia Laws should be repealed and none suffered to be re-enacted, & the Arms of all the People should be taken away, . . . nor should any Foundery or manufactuary of Arms, Gunpowder, or Warlike Stores, be ever suffered in America, nor should any Gunpowder, Lead, Arms or Ordnance be imported into it without Licence . . . .”

To the Americans of the Revolution and the Founding Era, the theory of some late-20th Century courts that the Second Amendment is a “collective right” and not an “individual right” might have seemed incomprehensible. The Americans owned guns individually, in their homes. They owned guns collectively, in their town armories and powder houses. They would not allow the British to confiscate their individual arms, nor their collective arms; and when the British tried to do both, the Revolution began. The Americans used their individual arms and their collective arms to fight against the confiscation of any arms. Americans fought to provide themselves a government that would never perpetrate the abuses that had provoked the Revolution.

What are modern versions of such abuses? The reaction against the 1774 import ban for firearms and gunpowder (via a discretionary licensing law) indicates that import restrictions are unconstitutional if their purpose is to make it more difficult for Americans to possess guns. The federal Gun Control Act of 1968 prohibits the import of any firearm that is not deemed “sporting” by federal regulators. That import ban seems difficult to justify based on the historical record of 1774-76.

Laws disarming people who have proven themselves to be a particular threat to public safety are not implicated by the 1774-76 experience. In contrast, laws that aim to disarm the public at large are precisely what turned a political argument into the American Revolution.

The most important lesson for today from the Revolution is about militaristic or violent search and seizure in the name of disarmament. As Hurricane Katrina bore down on Louisiana, police officers in St. Charles Parish confiscated firearms from people who were attempting to flee. After the hurricane passed, officers went house to house in New Orleans, breaking into homes and confiscating firearms at gunpoint. The firearms seizures were flagrantly illegal under existing state law. A federal district judge soon issued an order against the confiscation, ordering the return of the seized guns.

When there is genuine evidence of potential danger–such as evidence that guns are in the possession of a violent gang–then the Fourth Amendment properly allows no-knock raids, flash-bang grenades, and similar violent tactics to carry out a search. Conversely, if there is no real evidence of danger–for example, if it is believed that a person who has no record of violence owns guns but has not registered them properly–then militaristically violent enforcement of a search warrant should never be allowed. Gun ownership simpliciter ought never to be a pretext for government violence. The Americans in 1775 fought a war because the king did not agree.

Source: http://www.davekopel.org/2A/LawRev/american-revolution-against-british-gun-control.html